Heavy Data Processing in JavaScript Part 2: Beyond Web Workers

In part 1, we moved heavy computation off the main thread using Web Workers. The UI stayed responsive while a background thread crunched our 100k records. Problem solved, right?

Not quite. Web Workers have a hidden cost that becomes painfully obvious as your datasets grow: data cloning.

The Hidden Cost of postMessage

When you send a large JSON object to a worker via postMessage(), the browser runs the Structured Clone Algorithm. It recursively traverses your entire object tree, copies every value into a new memory space, and reconstructs the object for the worker.

For our 100k records, this means the browser is doing a deep copy of the entire dataset. That copying happens on the Main Thread—the very thread we're trying to keep free. So even though our heavy computation runs in the background, we still get a momentary freeze right when we send the data. And we're using double the memory: the original plus the clone.

Let's fix this.

Transferable Objects: Moving Instead of Copying

What if we could move data to a worker instead of copying it? That's exactly what Transferable Objects do.

The key insight is that ArrayBuffer (the raw binary data behind TypedArrays) can be transferred rather than cloned. When you transfer a buffer, you're handing over ownership of that memory block. The transfer is instant—zero-copy—regardless of how large the data is. The catch? Once you transfer it, the original thread loses access. The buffer becomes "detached" and has a length of zero.

To use this, we need to change how we think about our data. Instead of working with nice JavaScript objects, we convert everything to binary TypedArrays.

// Main Thread

const timestamps = new Float64Array(100000);

const values = new Int32Array(100000);

// ... fill arrays from JSON ...

// Transfer ownership to the worker

worker.postMessage(

{ timestamps, values },

[timestamps.buffer, values.buffer] // <-- Transfer list

);

// After this line, timestamps.length === 0

// The data now belongs to the workerThe magic is in that second argument to postMessage(). By listing the buffers there, we tell the browser: "Don't clone these—transfer them."

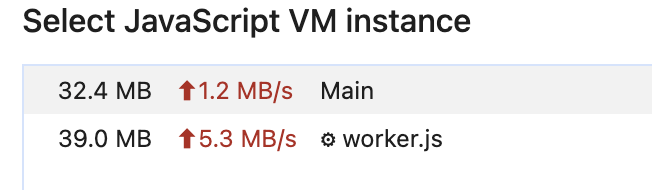

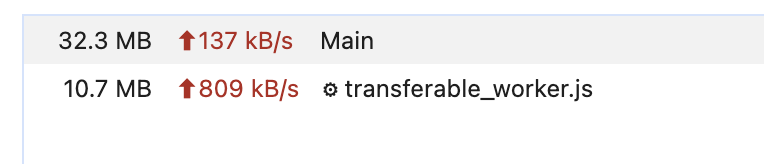

You can see the difference immediately in DevTools. With the standard worker, memory spikes as the data is duplicated. With transferables, it stays flat—the data just moves from one place to another.

See it in action: transferable.html

For most one-way data flows (send data to worker, get result back), transferable objects are the sweet spot. You get instant transfers with no memory overhead. The only downside is working with TypedArrays instead of regular objects, which requires a bit more bookkeeping.

SharedArrayBuffer: True Shared Memory

Transferable objects solved the copy problem, but they introduced a new limitation: once you transfer data to a worker, the main thread can't access it anymore. What if you need both threads to work with the same data?

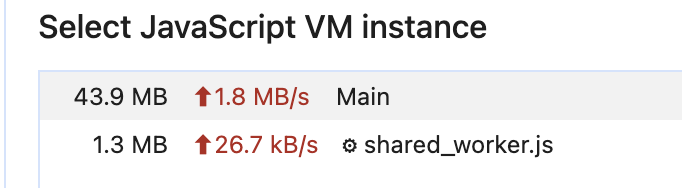

Enter SharedArrayBuffer. Unlike regular ArrayBuffers that get transferred or cloned, a SharedArrayBuffer creates a memory region that multiple threads can access simultaneously. No copying, no transferring—both threads see the exact same bytes.

// Main Thread

const sharedBuffer = new SharedArrayBuffer(1024);

const view = new Int32Array(sharedBuffer);

view[0] = 42;

// Send a reference (not a copy, not a transfer)

worker.postMessage({ buffer: sharedBuffer });

// Main thread still has access

console.log(view[0]); // 42// Worker

onmessage = (e) => {

const view = new Int32Array(e.data.buffer);

console.log(view[0]); // 42 - same memory!

view[0] = 100; // Main thread sees this change too

};This is true shared memory, just like you'd have in C or Rust with threads. You allocate a block, create "views" into it using TypedArrays, and both threads can read and write.

For our data processing scenario, we can pack multiple arrays into a single SharedArrayBuffer by calculating offsets:

const count = 100000;

const timestampBytes = count * 8; // Float64 = 8 bytes

const valueBytes = count * 4; // Int32 = 4 bytes

const totalBytes = timestampBytes + valueBytes;

const sharedBuffer = new SharedArrayBuffer(totalBytes);

const timestamps = new Float64Array(sharedBuffer, 0, count);

const values = new Int32Array(sharedBuffer, timestampBytes, count);

The Security Catch

There's a catch. SharedArrayBuffer was disabled in all browsers back in 2018 due to the Spectre vulnerability. It's back now, but only if your server sends specific security headers:

Cross-Origin-Opener-Policy: same-origin

Cross-Origin-Embedder-Policy: require-corpWithout these headers, SharedArrayBuffer will simply be undefined. This is the browser's way of protecting against timing attacks that could read memory across origins.

When Shared Memory Gets Tricky

For read-heavy workloads like our aggregation example, SharedArrayBuffer is straightforward. But when multiple threads write to the same memory, you enter the world of race conditions. If the main thread writes to view[0] while the worker reads it, you might get garbage. JavaScript provides Atomics for this—atomic operations and locks that prevent data corruption. That's a deep topic for another article.

WebAssembly: When JavaScript Isn't Fast Enough

So far, we've optimized how data moves between threads. But the actual computation is still JavaScript. For CPU-intensive numeric work, there's another level: WebAssembly.

WebAssembly (WASM) is a binary instruction format that runs in browsers at near-native speed. You write code in C, C++, or Rust, compile it to .wasm, and run it alongside your JavaScript. The key benefits are predictable performance (no JIT warmup, no garbage collection pauses), optimized numeric computation, and the ability to be 2-10x faster than JavaScript for tight loops.

WASM really shines for heavy math—image processing, physics simulations, cryptography, anything with tight loops over numeric data. It doesn't help with DOM manipulation or string operations, where JavaScript is often just as fast or faster.

Writing C for the Browser

Let's port our heavy calculation to C. Here's the computation we've been running in JavaScript:

The EMSCRIPTEN_KEEPALIVE macro prevents the compiler from removing our function during optimization. We compile with Emscripten:

emcc aggregate.c -O3 -s WASM=1 -s EXPORTED_FUNCTIONS='["_heavy_calc", "_malloc", "_free"]' -o aggregate.jsThis produces aggregate.wasm (the binary) and aggregate.js (the glue code that helps JavaScript talk to WASM).

Loading WASM in JavaScript

Loading a WASM module is straightforward:

const response = await fetch('aggregate.wasm');

const bytes = await response.arrayBuffer();

const { instance } = await WebAssembly.instantiate(bytes);

// Now you can call C functions directly

instance.exports.heavy_calc(dataPtr, count);The tricky part is memory management. WASM has its own linear memory space. To pass data in, you allocate memory inside WASM, copy your JavaScript data into it, run your function, and copy results out. It's like talking to a different process.

Combining WASM with Workers

For the best results, run WASM inside a Web Worker. This gives you both parallel execution and fast computation:

// wasm_worker.js

let wasmModule;

async function initWasm() {

wasmModule = await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(

fetch('aggregate.wasm')

);

}

initWasm();

self.onmessage = (e) => {

const { values } = e.data;

// Allocate memory in WASM's linear memory

const ptr = wasmModule.instance.exports.malloc(values.length * 4);

const wasmArray = new Float32Array(

wasmModule.instance.exports.memory.buffer,

ptr,

values.length

);

wasmArray.set(values);

// Process in WASM

wasmModule.instance.exports.heavy_calc(ptr, values.length);

// Read results back

const result = new Float32Array(wasmArray);

wasmModule.instance.exports.free(ptr);

self.postMessage({ result });

};Is it worth the complexity? The numbers speak for themselves. In our tests, the JavaScript version took around 5000ms to process the dataset. The WebAssembly version? About 4ms. That's not a typo—we're talking about a 1000x speedup for this particular workload.

Why such a dramatic difference? JavaScript has to do bounds checking on every array access, type checking on every operation, and the JIT compiler optimizes on the fly. WebAssembly compiles ahead of time to native machine code with fixed types, direct memory access, and no garbage collection pauses. For tight numeric loops like ours, it runs essentially as fast as native C code.

Of course, WASM isn't magic. The speedup depends heavily on the workload. For simpler operations, the overhead of copying data in and out of WASM memory might eat up the gains. But for compute-heavy tasks with large datasets, it's a game-changer.

Full source code including C examples

Putting It All Together

We've covered a lot of ground. Starting from a frozen UI, we progressed through increasingly sophisticated techniques:

Web Workers moved computation off the main thread, keeping the UI responsive. Simple and effective for most cases.

Transferable Objects eliminated the data cloning overhead by moving memory ownership instead of copying. Perfect for large datasets that flow one way.

SharedArrayBuffer gave us true shared memory between threads, useful when both need access to the same data. More powerful, but requires security headers and careful synchronization.

WebAssembly accelerated the computation itself, achieving near-native performance for numeric work. Worth the complexity when JavaScript becomes the bottleneck.

You don't need all of these. Start with a simple Web Worker. Profile your app. If data transfer is slow, try transferable objects. If you need shared access, consider SharedArrayBuffer. If the computation itself is too slow after all that, then reach for WASM.

The best optimization is the one you don't have to do. But when you do need it, these tools are waiting.