Understanding the 14KB Rule in Web Performance

You've probably seen pages that render instantly and others that hang on a blank screen for seconds. Often, the difference comes down to whether critical resources fit within the first network round trip—roughly 14KB.

This constraint comes from TCP's congestion control mechanism and has practical implications for how we structure our HTML and CSS.

TCP Slow Start and the Initial Congestion Window

When a browser opens a new TCP connection, the server doesn't send data at full speed. TCP uses slow start to probe network capacity and avoid congestion. The server begins with a small initial congestion window—typically 10 TCP segments (RFC 6928).

Each TCP segment carries approximately 1,460 bytes of payload (the Maximum Segment Size). This gives us: 10 × 1,460 ≈ 14,600 bytes for the first burst of data.

After transmitting these initial packets, the server waits for acknowledgment before sending more. This wait equals one Round Trip Time (RTT)—anywhere from 50ms on good connections to 300ms+ on mobile networks.

If everything needed to render above-the-fold content fits within that first ~14KB, the browser can begin painting immediately. If critical resources require additional requests, each one adds at least one more RTT to your First Contentful Paint.

The Render-Blocking Problem

CSS is render-blocking by design. When the browser encounters <link rel="stylesheet" href="styles.css">, it pauses rendering until that stylesheet is fetched and parsed. This prevents the flash of unstyled content, but it creates a dependency chain:

- Browser requests HTML

- Server responds with HTML (first round trip)

- Browser parses HTML, discovers external CSS reference

- Browser requests CSS file

- Server responds with CSS (second round trip)

- Rendering begins

On a 3G connection with 300ms RTT, that's 600ms minimum before first paint—assuming the CSS file itself fits within one congestion window. Larger stylesheets require additional round trips.

Measuring the Impact

I set up two identical pages to measure this effect. Both have the same content and final appearance, but one inlines critical CSS while the other loads it externally.

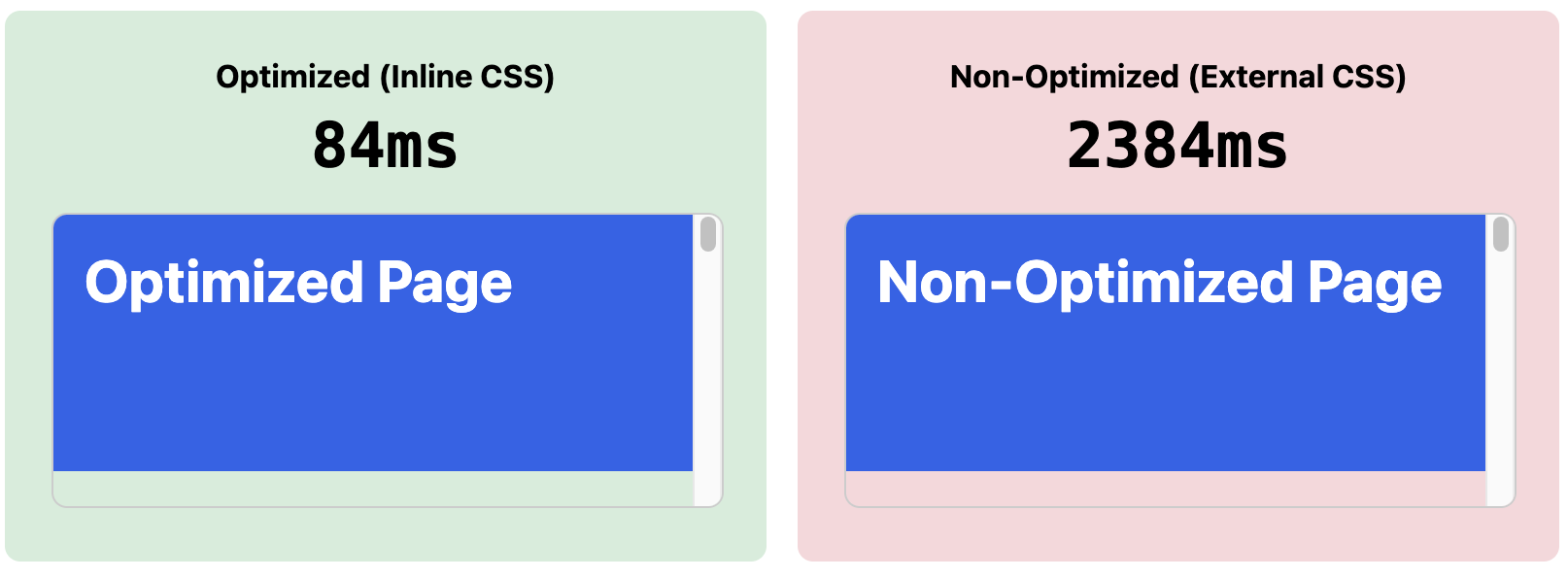

3G Network (simulated):

First Contentful Paint: 84ms (inline) vs 2,384ms (external). The external CSS version requires multiple round trips, and slower bandwidth compounds the delay.

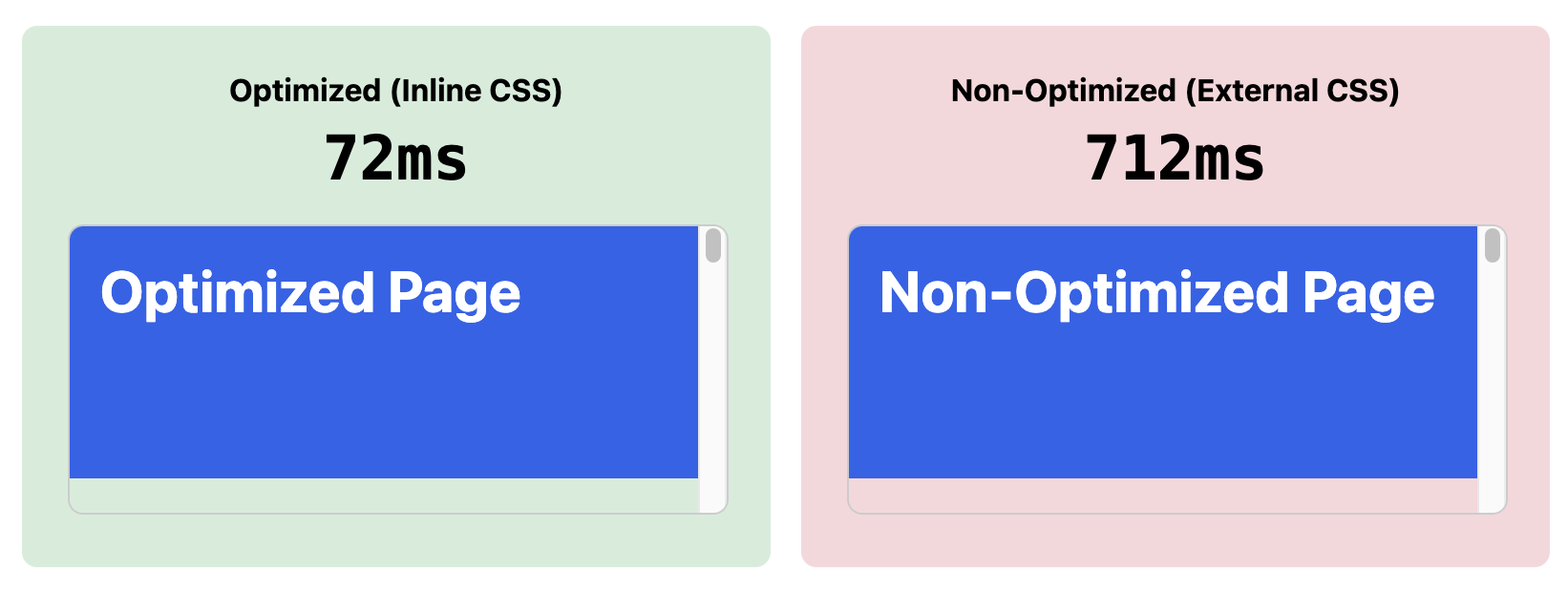

Slow 4G Network (simulated):

First Contentful Paint: 72ms (inline) vs 712ms (external). Even on faster networks, the additional round trip adds noticeable latency.

The 14KB Budget

With gzip or brotli compression, 14KB on the wire represents roughly 50-70KB of uncompressed content. Your goal is to fit the HTML document along with critical inline CSS within this compressed size. That's sufficient for most pages—the complete document structure, layout styles, typography, and colors for the initial viewport.

JavaScript has similar implications. Render-blocking scripts in the <head> add to the critical path. For scripts that must execute before render, they count against your 14KB budget. Non-critical JavaScript should use defer or async attributes to avoid blocking the first paint.

Inlining Critical CSS

The solution follows directly from the constraint: embed the CSS required for above-the-fold content directly in the HTML document.

<style>

.header { background: #2563eb; color: white; padding: 2rem; }

.hero { min-height: 400px; }

<!--...->

</style>This CSS travels with the HTML in the first response. The browser has everything needed to render immediately—no additional round trips required.

For the remaining styles—below-the-fold components, interactive states, third-party CSS—load them asynchronously:

<link rel="preload" href="styles.css" as="style" onload="this.rel='stylesheet'">

The browser fetches the full stylesheet without blocking render. Once loaded, it applies automatically. Users see content immediately while the complete styles load in the background.

Considerations

The 14KB figure is a guideline, not an absolute. CDNs often use larger initial congestion windows of 20-30 segments, and HTTP/3 with QUIC has different congestion control characteristics entirely. Repeat visitors benefit from connection reuse and caching, which can bypass slow start altogether. Server administrators can also adjust initcwnd values to increase the initial window. That said, targeting 14KB ensures good performance across the widest range of network conditions. First-time visitors on constrained networks—often the most important audience to optimize for—will benefit most from this approach.

Demo

See both versions side by side

Open DevTools, enable network throttling (Slow 3G), and click "Run Test". If your connection uses HTTP/3 (QUIC), the difference may be less dramatic due to 0-RTT connection resumption—try testing in an incognito window or over HTTP/2 for clearer results.

References

- RFC 6928: Increasing TCP's Initial Window — IETF

- Extract Critical CSS — web.dev